A sermon by the Rev. Dr. Thee Smith

Proper 6 – Year A

In the name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—One God. Amen.

On this Father’s Day today I share with you two stories about fathers and their children. We’re all familiar with the witty and winsome way in which children can remark upon our relationships and circumstances. Remarkably often children are able to capture the truth about our human reality in ways that often surpass our adult insight. A wry example is told about a three-year-old girl who one day asked her father a gender question.

“Daddy, can boys can wear dresses? Boys can wear dresses too, right?”

Her father thought for a moment before he gave her a ‘politically correct’ answer.

“Yes they can. Most boys don’t, but if they wanted to, they could.”

Now the little girl probably noticed her dad’s hesitation. But it’s unlikely that she was able to interpret that hesitation as his valiant effort to overcome any prejudice or bias against boys wearing dresses. You know the lingo: he did pretty well avoiding a reaction that would be critically described as heterosexist, or hetero-normative, or homophobic. When he said that “most boys don’t wear dresses, but could if they wanted to,” he was able to come up with a socially progressive answer to her question, right? Nonetheless for a little girl she was right on the mark herself when she advised him not to try it—when she said,

“Daddy, you wouldn’t look good in a dress; it’s not your style.”

That’s right, ‘It’s just not your style.’ www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/05/06/the-funniest-thing-your-kid-said_n_7213254.html

Now here I want to share with you another, more pertinent child’s remark to his father. This one is more pertinent today because it involves a key theological theme that’s represented by a classic Christian icon. It’s an Anabaptist icon that connects with the persecution theme in today’s gospel, where Jesus warns us that we will suffer for his name’s sake, and how to take that suffering; how to suffer as Christians. Now from a certain perspective this icon is “a piece of artwork that shouldn’t exist.” That’s because icon painting is best known as an Eastern Orthodox art tradition—and Anabaptists and the Orthodox have not been regarded as compatible with one another. “In spite of this fact, several years ago a series of icons was commissioned by a Bulgarian iconographer. The result was a truly stunning piece of artwork…based [on the well-known] etching of Dirk Willems rescuing his captor from certain death in an icy river.”

Dirk Willems (d.16 May 1569) was a 16th century Dutch martyr who is most famous for escaping from prison, then turning around to rescue his pursuer. That pursuer had fallen through thin ice while chasing Willems across a frozen river. After rescuing him from drowning Willems was recaptured, tortured, and killed for his faith (Wikipedia).

A couple of years ago a pastor with Anabaptist heritage pastor was sitting in his office with a copy of that icon on his desk and with his 2-year-old son, Levi, on his lap. As the pastor typed away at his computer his son was playing with something when he noticed the Willems icon and said, “Look, daddy — Jesus.”

This is how the pastor himself goes on to tell what happened next. First, he admits, “I’ve told the Dirk Willems martyr story numerous times.” And then he relates the following additional details.

[It’s] a story from the 1500s that is recounted in a large volume of stories of people who died for their faith titled The Martyrs Mirror. While the book contains martyr stories going all the way back to Jesus himself, most of the stories are of Anabaptists who either suffered or were killed for their faith.

As the story goes, Willems was captured and held prisoner in the middle of winter. He managed to escape at one point and was pursued by his jailers as he ran from the castle. As he escaped, he [crossed] a frozen river. One of his pursuers followed him onto the river and, being heavier than Willems, broke through the ice and fell into the [water]. Willems could have kept going but stopped and turned around and went back to save the life of his pursuer. This is the moment that is captured in the image. The story continues, however. After Willems rescues his pursuer, the pursuer wants to let him go. However, the head jailer, who is on the other side of the river, yells across to the other jailer and says, “If you don’t take Willems back into custody, you’ll be the one who burns at the stake.” Willems is then re-captured and eventually burned at the stake. Thus he loses his life to save his enemy.

Then the pastor goes on to observe that “for many Anabaptists, particularly for many Mennonites, this story has almost become a part of the biblical canon.” What is interesting, he says next, “is that when this story is told, almost universally Willems is seen as the Jesus character.”

The implied message is that Willems is loving his enemies just like Jesus loved his enemies, and that we should do the same. That’s why when my son said, “Look, daddy — Jesus,” I was very pleased, but not particularly surprised. It’s what he said after that that took me off guard.

[When] Levi pointed to the icon and said, “Look, daddy — Jesus.” I said, “Where is Jesus? Jesus is on the water?” Levi then replied, “No, daddy; Jesus is in the water.” That’s when my jaw hit the floor and a significant light bulb went on in my head.

For virtually my whole life I had experienced and told this story thinking that Willems was the Jesus figure in the story. But what if he’s not? What if the jailer in the water is Jesus? What if the reason that Willems turned around and saved the life of his jailer was not because Willems was suddenly filled with the spirit of Christ, but instead Willems turned around because he recognized the spirit of Christ in his enemy drowning in the water?

And here the pastor concludes:

This revelation out of the mouth of a babe has significantly shifted the moral of the Dirk Willems story for me. Previously the message was that we as Christians are called to be more Christ like and love our enemies just as Willems did. But now the message is that as Christians we are called to love our enemies because they hold the presence of Christ. This is a shift in perspective that might be small, but that holds the potential to turn our world upside-down. It already has for me.

Alan Stucky is the pastor of First Church of the Brethren in Wichita, Kansas.

http://mennoworld.org/2016/01/04/the-world-together/in-the-dirk-willems-story-who-represents-christ/

Now how could that pastor’s new insight serve to “turn our world upside-down?” For my part, I’m reminded here of Mother Teresa’s compelling charge to her Missionary Sisters of Charity. Again and again she commanded them to pick up and minister to the dead and dying bodies of people on the streets of Calcutta; but to do so as if they were serving Jesus himself—as she said, serving Jesus “in his distressing disguise of the poor.” That’s right; they were to act as if serving Jesus himself, “in his distressing disguise of the poor.” Thus they learned not to see themselves as Christ but to see Christ himself in the sick and the maimed, the abandoned and the brutalized; to see him in them, and to be loving Jesus as they handled, washed and cleaned those bodies. Yes, as they touched and cherished those bodies they were to be cherishing the precious body of Christ himself.

Now, in today’s scripture reading in Romans, appointed this year for this first Lord’s Day after Trinity Sunday, we read this declaration in the eighth verse, chapter 5:

But God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us. —Romans 5:8

“While we still were sinners Christ died for us.” It’s an arresting claim, isn’t it? And it has riveted my attention all week. I’d like you to imagine with me that our loving Lord sees us in all our distress, sees us in all our imperfections and failures, shortcomings and vicious behavior toward one another, our hatred, our enmity and resentments, our inability to care for and cherish others with compassion; he sees the ugliness of our souls—our sin-stained souls, and loves us anyway. Yes, “while we were still sinners,” in our distressing guise, Christ died for us.

In his commentary on that verse my old seminary professor, Reginald Fuller, expounds it this way. He reminds us that Christ’s love of sinners was grounded in unconditional love; a love that the New Testament privileged with that Greek word, agape. By comparison with that standard, most ordinary love comes with ‘strings attached.’ It is conditional or depends upon the attractive qualities of the thing or person being loved. “Agape” on the other hand, “means love entirely uncaused by the attractiveness of its object.” In that regard he also calls it “completely selfless.” That selflessness contrasts with conventional love that is “evoked precisely by the object’s attractiveness.” Conditional love is “essentially self-regarding” rather than other-regarding. It operates as if to say, “What do I require of you in order for me to be attracted to you?”

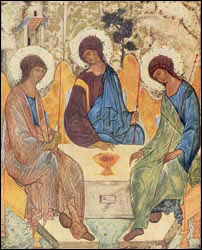

The challenge of agape is how to love others for their own sake, rather than regarding each other exclusively or primarily for our own sake. That’s what I want to explore with you in today’s scriptures, on this first Lord’s Day after Trinity Sunday. From now going forward into the long season of Pentecost we have at last all the divine persons of the Holy Trinity represented ‘at the table,’ so to speak. So we can now proceed to explore some implications of their most sacred unity. A key implication for us is how the love expressed in that Trinitarian unity impacts our human regard for one another. In that connection we have another inspired icon of holy love to gaze upon. Consider that classic icon of the Holy Trinity, painted in the 15th century by the Russian iconographer, Andrei Rublev. And let’s observe how the triune love pictured there also challenges us to renew and reclaim our human unity.

You may well know the icon I’m talking about. And you may already have observed that is remarkably represents the story of Abraham and Sarah that is appointed in many of our Anglican and Episcopal churches for today. In that connection Rublev’s icon also depicts the mysterious appearance of the three travelers or three angels to Abraham and Sarah under the oaks of Mamre.

In Rublev’s icon the persons of the Holy Trinity are shown in the order in which they are confessed in the [Apostle’s and Nicene creeds]. The first angel [on the left] is the first person of the Trinity - God the Father; the second, middle angel is God the Son; the third angel is God the Holy Spirit. And all three angels are blessing the chalice, in which lies the sacrificial calf that Abraham and Sarah prepared in hospitality for their visitors to eat. The sacrifice of the calf signifies the Savior’s death on the cross [as the lamb of God], while its preparation as food symbolizes the sacrament of the Eucharist. www.holy-transfiguration.org/library_en/lord_trinity_rublev.html

In Rublev’s icon the persons of the Holy Trinity are shown in the order in which they are confessed in the [Apostle’s and Nicene creeds]. The first angel [on the left] is the first person of the Trinity - God the Father; the second, middle angel is God the Son; the third angel is God the Holy Spirit. And all three angels are blessing the chalice, in which lies the sacrificial calf that Abraham and Sarah prepared in hospitality for their visitors to eat. The sacrifice of the calf signifies the Savior’s death on the cross [as the lamb of God], while its preparation as food symbolizes the sacrament of the Eucharist. www.holy-transfiguration.org/library_en/lord_trinity_rublev.html

In that connection Catholic churches today observe the Solemnity of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ—more traditionally known as the feast of Corpus Christi; where the word, corpus, means ‘body:’ corpus Christi—‘body of Christ.’

Now significantly for us, by their bodily posture all three persons are also deferring to one another in theologically significant ways. God the Father is inclining toward both God the Son and God the Holy Spirit, and each of them in turn is inclining toward God the Father. Thus the unity of divine persons provides a model for our human unity: we too are meant to love other persons by deferring to one another with the same regard that the blessed persons of the Holy Trinity defer to each other.

That would mean a practice of loving other persons for their own sake, unconditionally, and not because of their attractiveness to us, but for each person’s own sake; because they too are a being of infinite value and worth, co-created like us by God. Thus we are loved not based on our attractions but on our created position in the divine economy.

On the basis of our co-created status with all other human beings we too can respond as Jesus did in today’s gospel, where it says that when he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.

Therefore he committed to be that shepherd, when said to his disciples,

"The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest."

Church family and friends, we are those laborers, and as Jesus commissioned the twelve apostles, we too are commissioned, and as he gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to cure every disease and every sickness (Matthew 9:36-10:1)—so we are called to make our life and times a proving ground for the unconditional, agape love of God. It is a love that does not require the condition that we are already godly before being loved or before loving others, but ‘proves that while we’re still sinners’ we’re already loved and can also love others. And isn’t that what we all deeply yearn for—to be loved just as we are, strengths and weaknesses, successes and failures, virtues and faults? As we more and more grant that to one another, how heavenly this earthly life becomes! God grant that we may more and more do so, in the name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.